Reading 1: Anthropomorphism and Anthropodenial

28 January 2019

It was above all the examination of concepts of architectural theory that made me familiar with anthropomorphism during my architectural studies in Vienna. Anthropomorphism generally describes the allocation of human qualities to non-human things and other living beings, such as animals, gods, or forces of nature. These qualities can be expressed both in form and behaviour.

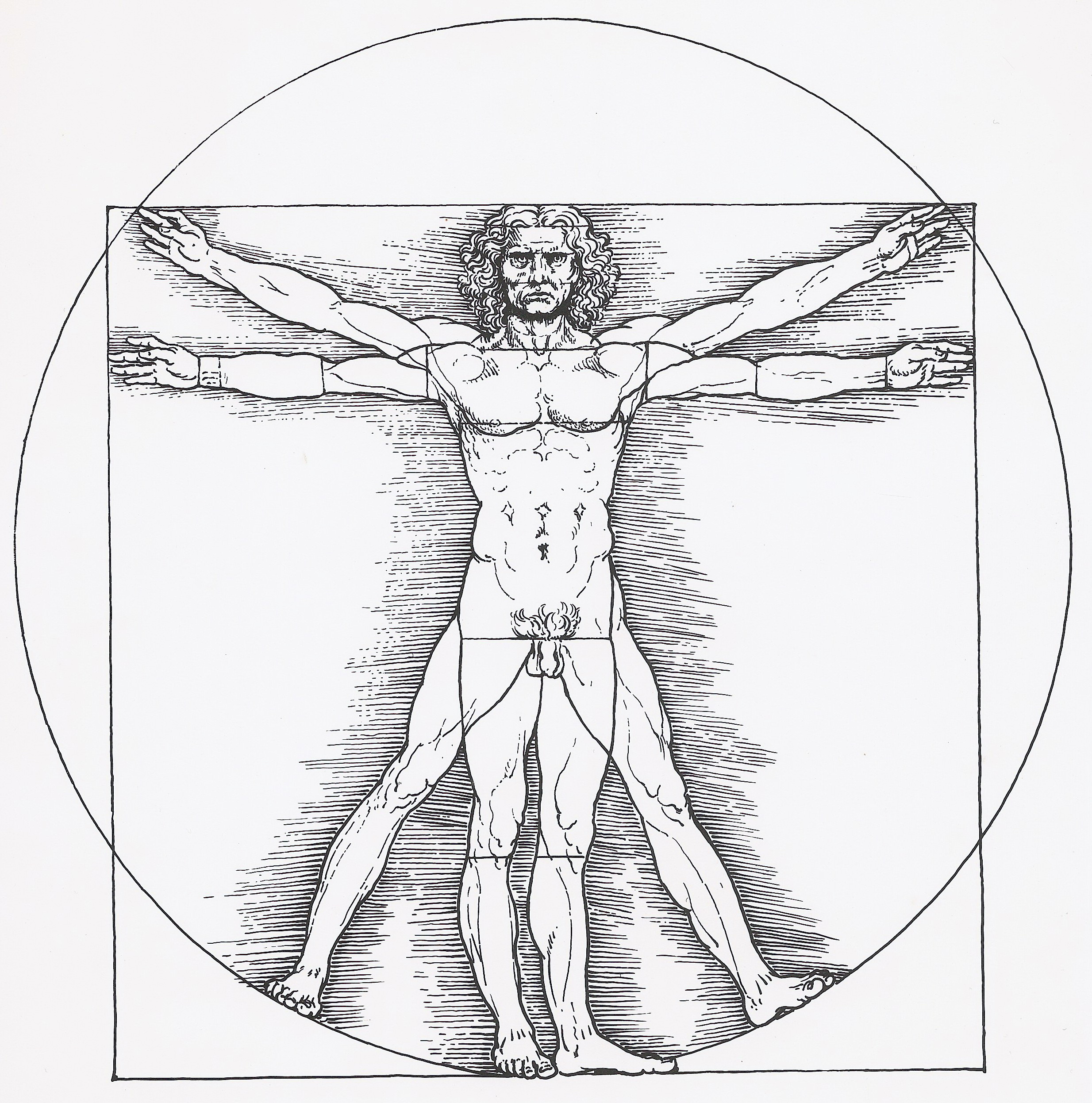

In architecture and the art of construction, anthropomorphism has always played an important role as a form of thought. Especially in theoretical reflections on buildings and their parts, architects and architectural theorists use the metaphor of the human body, which for a long time was even regarded as a direct symbolic image of architecture and its parts. In the sense of this anthropomorphistic architectural concept, both the human body and the building were precisely defined with the help of measurements, numbers, proportions and geometric figures, but above all described metaphorically. The first comparisons between the bodies of buildings and people can be found in the only preserved architectural treatise of antiquity: Vitruv's "De architectura libri decem". There Vitruv writes, for example, that the design of sacred architecture is based on symmetry and proportion and that this design corresponds to the correct composition of the human body. At another point Vitruv refers to the origin of the Doric column, the proportioning of which is to be derived from the proportions of a man's physique. The view of the anthropomorphically conceived building, as it was formulated in Vitruvius and then especially in the Renaissance architecture of the 15th century, was undoubtedly not an instruction set that directly should be implemented in architecture, but rather a metaphorically meant comparison. No building was actually given the form of the human body, only the abstract architectural idea on which the design of the building was based on, was oriented towards an anthropomorphic concept.

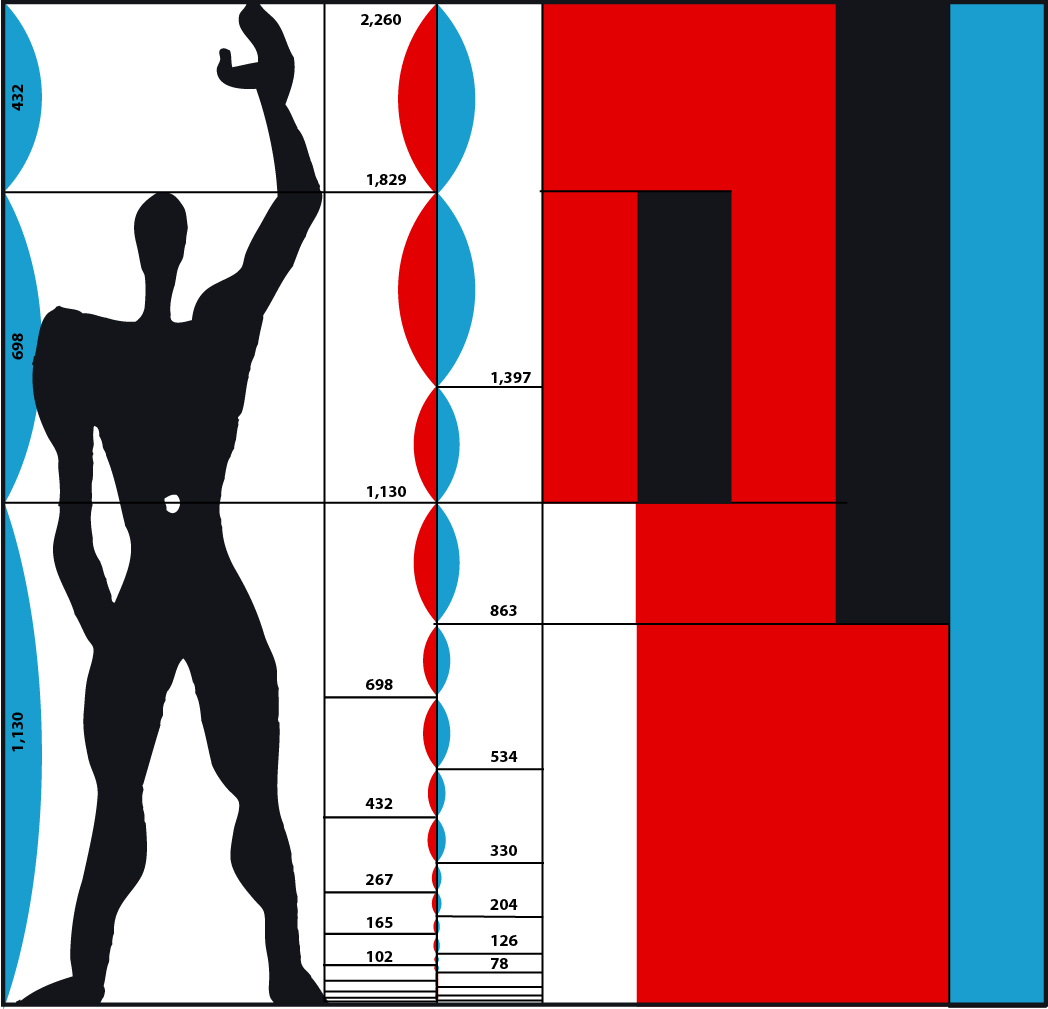

Another well-known example of anthropomorphism in architecture dates back to the first half of the twentieth century. Developed by the French architect Le Corbusier in 1947, the "Modulor" was intended to serve as a modular system and basic measure of standardized mass production and was designed to meet the following requirements: it had to correspond to the average dimensions of man and be based on a mathematical basis and the laws of proportion of nature. In addition, Le Corbusier hoped that his new measurement system would overcome the contrast between the meter and the anthropomorphic measurement system of foot and inch used in Anglo-American culture.

Personally, anthropomorphism and the consequent confrontation with human beings and their physical proportions, based on the model of Vitruv or Le Corbusier, has had a strong influence on me in my development as an architect and later during my work as a user experience designer. At the beginning of my architectural studies, it was very helpful to derive room sizes, heights and building proportions from people's proportions. In addition, it was important to me to incorporate into my work, a great deal of empathy for the future user of my product and to place him with his individual needs and wishes at the centre of the discussion. In the end, it was always a matter of concern to me to understand the context in which my project moves. I would like to remain true to these working methods during the Design in Safaris Collab. The reading of Anthropomorphism and Anthropodenial: Consistency in Our Thinking about Humans and Other Animals by Frans B. M. de Waal showed me above all what is important when dealing with animals and their behaviour. I am of the opinion that animals are very empathic and social creatures that behave similar to humans according to learned patterns in their social structures, communities and networks. It is my concern to further explore and understand these behaviors according to the concept of animalcentric anthropomorphism described by de Waal, to take perspective and to look at behavior as much as possible from the animal’s perspective in order to understand where this behavior is deriving from.